Historical Characters You’ll Find in Rebecca Harper’s Travels …

Hiram P. Merritt, of Merritt Station, Yolo County, (my great-great-grandparent) the most extensive breeder of live-stock in Northern California, is a representative of the best type of the American business man. Like most men who have achieved distinction in their respective callings, he started in life without capital save a fine physical organization and an active and well-poised brain.

A pioneer of 1850, he came here a young man, and after passing through more than the usual vicissitudes and reverses of those early days, he has by industry, economy and shrewd judgment long stood in the front ranks of Yolo County’s wealthy, influential citizens. Dr. Merritt was born January 24, 1830, in Fairhaven, Rutland County, Vermont.

His father, Noble Merritt, was a lumberman. His mother’s name before marriage was Elizabeth Bates. He was three years of age when his parents moved to Allegany County, New York, by way of Lake Champlain and Erie Canal.

In their new home his father engaged in the lumber business, as that portion of the State of New York was then a dense forest; and here young Hiram assisted his father to the extent of his ability, thus forming the habits of industry which he still retains, although of late years his heavy work has been more of the intellectual kind.

As the prospects in Western New York for business with the commercial world were not satisfactory to his ambition, he started for the West in company with his uncle, Sydney Merritt, as far as Detroit, and alone to Indiana.

On starting, his cash capital was only $15, and arriving at South Bend, Indiana, he found his capital reduced to $2.50. Here he first secured employment in a drug store, which place he retained for six years, receiving as compensation only his necessary expenses, with the privilege of studying medicine.

By diligence and economy, and occasional practice at dentisty, he became able to attend medical lectures and graduate at the State Medical College of Indiana, in the spring of 1849. Returning to South Bend, he followed his chosen profession, in partnership with his old preceptor.

His father sent him $100 at the beginning of his practice for the purchase of a horse to use in attending calls. He gave $25 of this to an aunt to keep for him, with the intention of coming to California, which he did the next year – 1850.

He joined an Indiana party, comprising the Wall Brothers (now of Denver), Dan W. Earl, of San Francisco, and others.

At Council Bluffs he utilized his medical knowledge in a small-pox epidemic, vaccinating the multitudes as he sat upon the wagon-seat. He also had many occasions to exercise his medical skill while crossing the plains.

The party arrived in Sacramento in August. The first business in which Dr. Merritt engaged after arriving her was that of running a meat-market, at Bridgeport, on the South Yuba, and financially he was successful.

In three months he sold out, went to the North Fork of the Cosumnes River, in Placer County, intending to follow the practice of medicine; and while residing there he became famous as a hunter.

On one occasion, while out hunting deer, he was shot at by an Indian, the ball striking the rock on which he was sitting and throwing the splinters into his face.

At another time he was engaged with a party of miners in a skirmish against Indians who had stolen their horses and mules, and in this engagement about thirty Indians were killed.

But, as the settlers were few and there was but little sickness among them, and as the Doctor had no taste for mining, he would have returned East could he have collected money enough and continued his medical studies in Philadelphia.

As it has turned out, however, it is probably for the best for him that he remained in this State. On the first day of January, 1851, he passed through Yolo County the first time, being at the time engaged in transporting merchandise by mule pack-train between Sacramento, Scott’s River, Yreka and other points north, a distance of 400 miles; and although his capital was small, he made money.

Going next to Carson Valley, with some $2,000, he did a prosperous business buying cattle, horses and mules of emigrants on their way to California and selling them to settlers in the Sacramento Valley.

After thus accumulating considerable money he entered farming pursuits on an extensive scale in Yolo County; but the first effort was a failure. Yet he took courage and began to retrieve his fortune by returning to Carson City and resuming his old trade with the emigrants.

He did not undertake to wait in idleness for his grain to grow, as most others did, but improved his time in trading. He adhered to his agricultural pursuits until about three years ago, when he rented all his agricultural lands in Yolo County, since which time he has been occupied looking after his extensive stock-breeding farms and other interests.

Thus he has been busily employed every season since he first came to the State, except that of 1856, when he made a visit to the East; but even this time he utilized the opportunity by bringing with him a herd of horses, which he disposed of profitably after his arrival here.

Although he early abandoned his medical profession, his knowledge of hygiene and medicine has doubtless been of great benefit to him through this long period.

He has made some money, of course, by the natural rise in the value of his lands, and has become by far the most extensive stock-raiser and mule-breeder in Central California, having grazing grounds in several other parts of the State besides Yolo County, and also in Nevada.

In Yolo County alone he has over 4,500 acres of good land; the exact number of acres cannot be told without a study of the public records, and is the largest land-owner in the county. He has 2,500 acres of the finest land where he resides, at Merritt Station, which point is named after him.

It is on the line of the railroad between Woodland and Davisville, whence as much grain is shipped as from any other point on the road. The Doctor has 14,000 acres in Trinity and Mendocino counties, devoted to grazing and breeding mules and cattle.

On an extensive tract in Nevada he has 30,000 sheep or more. He is one of the original owners in the great Seventy-six Canal in Fresno and Tulare counties, which serves to irrigate immense tracts of land. It is one of the most gigantic enterprises of the kind in California.

The Doctor’s example has ever shown that he is a firm believer, not in luck, but in untiring industry. He has been President of the Bank of Yolo ever since its organization.

He has made two trips to the Eastern States, and in 1878 he made a trip across the Atlantic, visiting Great Britain and various points on the continent of Europe; was in Paris during the great exposition of that year.

He is so firm a believer in the capacities of the soil and climate of Central and Northern California that he really maintains that an industrious man can not only make a living off of ten acres of ground here, but actually lay up money.

In view of this fact he holds that the price of land here is absurdly low.The Doctor was married May 26, 1868, to Miss Jeannette E. Hebron, and has two sons and two daughters.

The sons, Alanson A. and George N., are both with their father, and by both inheritance and training they are exemplary young men, having been brought up to appreciate the utility of industry.

Note: Lanson is my great grandfather. He died after the birth of my grandmother of a ruptured appendix. The house burned shortly after my grandmother was born.

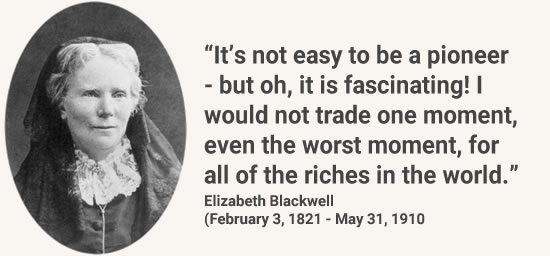

Elizabeth Blackwell (February 3, 1821 – May 31, 1910) was a British physician, notable as the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States, and the first woman on the Medical Register of the General Medical Council.

Blackwell played an important role in both the United States and the United Kingdom as a social awareness and moral reformer, and pioneered in promoting education for women in medicine. Her contributions remain celebrated with the Elizabeth Blackwell Medal, awarded annually to a woman who has made significant contribution to the promotion of women in medicine.

Blackwell was initially uninterested in a career in medicine, especially after her schoolteacher brought in a bull’s eye to use as a teaching tool. Therefore, she became a schoolteacher in order to support her family.

This occupation was seen as suitable for women during the 1800s; however, she soon found it unsuitable for her. Blackwell’s interest in medicine was sparked after a friend fell ill and remarked that, had a female doctor cared for her, she might not have suffered so much.

Blackwell began applying to medical schools and immediately began to endure the prejudice against her sex that would persist throughout her career. She was rejected from each medical school she applied to, except Geneva Medical College, currently known as State University of New York Upstate Medical University, in which the male students voted for Blackwell’s acceptance.

Thus, in 1847, Blackwell became the first woman to attend medical school in the United States. Blackwell’s inaugural thesis on typhoid fever, published in 1849 in the Buffalo Medical Journal, shortly after she graduated, was the first medical article published by a female student from the United States.

It portrayed a strong sense of empathy and sensitivity to human suffering, as well as strong advocacy for economic and social justice. This perspective was deemed by the medical community as feminine.

Blackwell also founded the New York Infirmary for Women and Children with her sister Emily Blackwell in 1857, and began giving lectures to female audiences on the importance of educating girls. She also played a significant role during the American Civil War by organizing nurses.

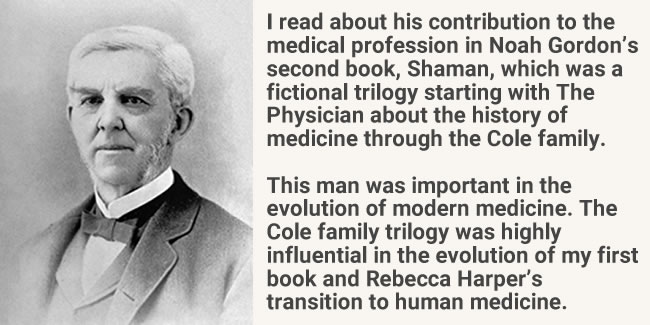

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. was an American physician, poet, and polymath based in Boston. Grouped among the fireside poets, he was acclaimed by his peers as one of the best writers of the day. His most famous prose works are the “Breakfast-Table” series, which began with The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table (1858).

He was also an important medical reformer. In addition to his work as an author and poet, Holmes also served as a physician, professor, lecturer and inventor and, although he never practiced it, he received formal training in law.

Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Holmes was educated at Phillips Academy and Harvard College. After graduating from Harvard in 1829, he briefly studied law before turning to the medical profession.

He began writing poetry at an early age; one of his most famous works, “Old Ironsides”, was published in 1830 and was influential in the eventual preservation of the USS Constitution.

Following training at the prestigious medical schools of Paris, Holmes was granted his Doctor of Medicine degree from Harvard Medical School in 1836.

He taught at Dartmouth Medical School before returning to teach at Harvard and, for a time, served as dean there. During his long professorship, he became an advocate for various medical reforms and notably posited the controversial idea that doctors were capable of carrying puerperal fever from patient to patient.

Holmes retired from Harvard in 1882 and continued writing poetry, novels and essays until his death in 1894.

Surrounded by Boston’s literary elite—which included friends such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and James Russell Lowell—Holmes made an indelible imprint on the literary world of the 19th century.

Many of his works were published in The Atlantic Monthly, a magazine that he named. For his literary achievements and other accomplishments, he was awarded numerous honorary degrees from universities around the world.

Holmes’s writing often commemorated his native Boston area, and much of it was meant to be humorous or conversational. Some of his medical writings, notably his 1843 essay regarding the contagiousness of puerperal fever, were considered innovative for their time.

He was often called upon to issue occasional poetry, or poems written specifically for an event, including many occasions at Harvard. Holmes also popularized several terms, including Boston Brahmin and anesthesia. He was the father of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. of the Supreme Court of the United States.

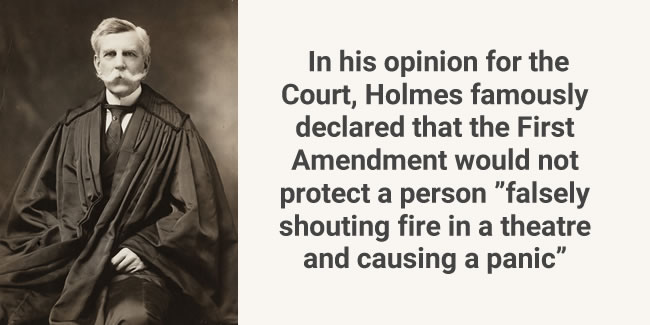

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (March 8, 1841 – March 6, 1935) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1902 to 1932.

Noted for his long service, concise and pithy opinions, and deference to the decisions of elected legislatures, he is one of the most widely cited United States Supreme Court justices in history.

Particularly for opinions on civil liberties and American constitutional democracy, and is one of the most influential American common law judges, honored during his lifetime in Great Britain as well as the United States.

Holmes retired from the court at the age of 90, an unbeaten record for oldest justice on the federal Supreme Court (although John Paul Stevens was only 8 months younger when he retired on April 12, 2010).

He previously served as an Associate Justice and as Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, and was Weld Professor of Law at his alma mater, Harvard Law School.

Profoundly influenced by his experience fighting in the American Civil War, Holmes helped move American legal thinking towards legal realism, as summed up in his maxim: “The life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience.”

Holmes espoused a form of moral skepticism and opposed the doctrine of natural law, marking a significant shift in American jurisprudence.

In one of his most famous opinions, his dissent in Abrams v. United States (1919), he wrote that he regarded the United States Constitution’s theory:

“… that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market” as “an experiment, as all life is an experiment” and believed that as a consequence “we should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions that we loathe and believe to be fraught with death.”

During his tenure on the Supreme Court, to which he was appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt, he supported the constitutionality of state economic regulation and advocated broad freedom of speech under the First Amendment.

Although, previously, in the 1919 case, Schenck v. United States, he had upheld criminal sanctions against draft protestors with the memorable maxim that “free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic”, and formulated the groundbreaking “clear and present danger” test for a unanimous court.

His positions as well as his distinctive personality and writing style made him a popular figure, especially with American progressives. His jurisprudence influenced much subsequent American legal thinking, including the judicial consensus supporting New Deal regulatory law, and influential schools of pragmatism, critical legal studies, and law and economics.

He was one of only a handful of justices to be known as a scholar; The Journal of Legal Studies has identified Holmes as the third-most cited American legal scholar of the 20th century.

Clara Barton achieved widespread recognition by delivering lectures around the country about her war experiences in 1865–1868.

During this time she met Susan B. Anthony and began an association with the woman’s suffrage movement. She also became acquainted with Frederick Douglass and became an activist for civil rights.

After her countrywide tour she was both mentally and physically exhausted and under doctor’s orders to go somewhere that would take her far from her current work.

She closed the Missing Soldiers Office in 1868 and traveled to Europe. In 1869, during her trip to Geneva, Switzerland, Barton was introduced to the Red Cross and Dr. Appia; he later would invite her to be the representative for the American branch of the Red Cross and help her find financial benefactors for the start of the American Red Cross.

She was also introduced to Henry Dunant’s book A Memory of Solferino, which called for the formation of national societies to provide relief voluntarily on a neutral basis.

In the beginning of the Franco-Prussian War, in 1870, she assisted the Grand Duchess of Baden in the preparation of military hospitals and gave the Red Cross society much aid during the war.

At the joint request of the German authorities and the Strasbourg Comité de Secours, she superintended the supplying of work to the poor of Strasbourg in 1871, after the Siege of Paris, and in 1871 had charge of the public distribution of supplies to the destitute people of Paris.

At the close of the war, she received honorable decorations of the Golden Cross of Baden and the Prussian Iron Cross.

When Barton returned to the United States, she inaugurated a movement to gain recognition for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) by the United States government. In 1873, she began work on this project.

In 1878, she met with President Rutherford B. Hayes, who expressed the opinion of most Americans at that time which was the U.S. would never again face a calamity like the Civil War.

Barton finally succeeded during the administration of President Chester Arthur, using the argument that the new American Red Cross could respond to crises other than war such as natural disasters like earthquakes, forest fires, and hurricanes.

Barton became President of the American branch of the society, which held its first official meeting at her I Street apartment in Washington, DC, May 21, 1881. The first local society was founded August 22, 1881 in Dansville, Livingston County, New York, where she maintained a country home.

The society’s role changed with the advent of the Spanish–American War during which it aided refugees and prisoners of the civil war.

Once the Spanish–American War was over the grateful people of Santiago built a statue in honor of Barton in the town square, which still stands there today. In the United States, Barton was praised in numerous newspapers and reported about Red Cross operations in person.

Barton on a 2021 stamp of Armenia.

Domestically in 1884 she helped in the floods on the Ohio river, provided Texas with food and supplies during the famine of 1887, took workers to Illinois in 1888 after a tornado, and that same year took workers to Florida for the yellow fever epidemic.

Within days after the Johnstown Flood in 1889, she led her delegation of 50 doctors and nurses in response. In 1896, responding to the humanitarian crisis in the Ottoman Empire of the Hamidian massacres, Barton arrived in Constantinople February 15.

Barton along with Minister Terrell spoke with Tewfik Pasha, the Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs, to procure the right to enter the interior. Barton herself stayed in Constantinople to conduct the business of the expedition.

Her General Field Agent, J. B. Hubbell, M.D.; two Special Field Agents, E. M. Wistar and C. K. Wood; and Ira Harris M. D., Physician in Charge of Medical Relief in Zeitoun and Marash, traveled to the Armenian provinces in the spring of 1896, providing relief and humanitarian aid.

Barton also worked in hospitals in Cuba in 1898 at the age of 77. Barton’s last field operation as President of the American Red Cross was helping victims of the Galveston hurricane in 1900. The operation established an orphanage for children.

As criticism arose of her mixing professional and personal resources, Barton was forced to resign as president of the American Red Cross in 1904 at the age of 83 because her egocentric leadership style fit poorly into the formal structure of an organizational charity.

She had been forced out of office by a new generation of all-male scientific experts who reflected the realistic efficiency of the Progressive Era rather than her idealistic humanitarianism.

In memory of the courageous women of the civil war, the Red Cross Headquarters was founded. During the dedication, not one person said a word. This was done in order to honor the women and their services. After resigning, Barton founded the National First Aid Society.

Julia Bulette is an interesting character that I happened upon while I was creating a character for my dear friend Pamala Wilkins.

I have a dear friend who is a vet. She is a horse doctor, like me. She was named the top vet at World Equine Veterinary Association in 2018. While we have only met once, she has helped me with personal and professional issues over many years.

She asked to be named in one of my books. So I asked her if she wanted to be a good guy or a bad guy. Her response was classic. “I want to be a floozy with a heart of gold.”

Hmm, either I would nail this and secure our friendship, or wham, I would be kicked to the curb. So I wrote one of my more enduring episodes, and hopefully, she will be happy. Fingers crossed.

It turns out that in history, this woman actually existed! Julia Bulette was just that. She was one of the greatest benefactors in Virginia City’s history.

Juliette “Julie” Bulette was born in London and moved to New Orleans with her family in the late 1830s. In about 1852 or 1853, she moved to California, where she lived in various places until her arrival in 1859 in Virginia City, Nevada, a mining boomtown since the Comstock Lode silver strike that same year.

As she was the only woman in the area, she became greatly sought after by the miners. She quickly took up prostitution. Jule, or Julia (as she became known), was described as a beautiful, tall, and slim brunette with dark eyes, and refined in manner with a humorous, witty personality.

“Jule” Bulette lived and worked out of a small rented cottage near the corner of D and Union streets in Virginia City’s entertainment district. An independent operator, she competed with the fancy brothels, streetwalkers, and hurdy-gurdy girls for meager earnings.

Contemporary newspaper accounts of her gruesome murder captured popular imagination. With few details of her life, twentieth-century chroniclers elevated the courtesan to the status of folk heroine, ascribing to her the questionable attributes of wealth, beauty, and social standing. In reality, Bulette was ill and in debt at the time of her death.

She was also a good friend to the miners, who adored her. One described her as having “caressed Sun Mountain with a gentle touch of splendor”.

Bulette supported the miners at times of trouble and misfortune, once turning her Palace into a hospital after several hundred men became ill from drinking contaminated water.

She nursed the men herself. Once when an attack by local American Indians appeared imminent, she chose to remain behind with the miners instead of seeking shelter in Carson City. She also raised funds for the Union cause during the American Civil War.

Bulette’s greatest triumph occurred when the firefighters made her an honorary member of Virginia Engine Number 1.

On 4 July 1861, the firemen elected her the Queen of the Independence Day Parade, and she rode Engine Company Number One’s fire truck through the town wearing a fireman’s hat and carrying a brass fire trumpet filled with fresh roses, the firemen marching behind.

She donated large sums for new equipment and often personally lent a hand at working the water pump.

On the morning of January 20, 1867, Bulette’s partially naked body was found by her maid in her bedroom. She had been strangled and bludgeoned to death.

Virginia City went into mourning for her, with the mines, mills and saloons being closed down as a mark of respect.

On the day of her funeral, January 21, thousands formed a procession of honor behind her black-plumed, glass-walled hearse; first the firemen, who were followed by the Nevada militia who played funeral dirges. Bulette was buried in the Flower Hill Cemetery.

A little over a year later, John Millain, a French drifter, was arrested and charged with the crime. On April 24, 1868, he went to the gallows, swearing he was not guilty of having killed Bulette, but had been only an accomplice in the theft of her meager belongings. Millain’s hanging was witnessed by author Mark Twain.

Bulette’s legend continued after her death. The Virginia and Truckee Railroad honored her memory by naming one of its richly furnished club coaches after her.

Her portrait hung in many Virginia City saloons, and author Rex Beach immortalized her as Cherry Malotte in his novel, The Spoilers. Oscar Lewis in his book Silver Kings reported that Bulette was written about more than any other woman of the Comstock Lode bonanza.

Only two authentic portraits exist of Bulette; one is a photograph which shows her standing beside an Engine Number 1 fireman’s hat. A third photograph, previously identified as her, was most likely that of her maid, who was also named Julia.

The television show Bonanza aired an episode called “The Julia Bulette Story” (Season 1, Episode 6, October 17, 1959) in which Julia is portrayed by actress Jane Greer.

The Virginia City chapter of E Clampus Vitus, a men’s historical society, is named #1864 “Julia C Bulette” in her honor.